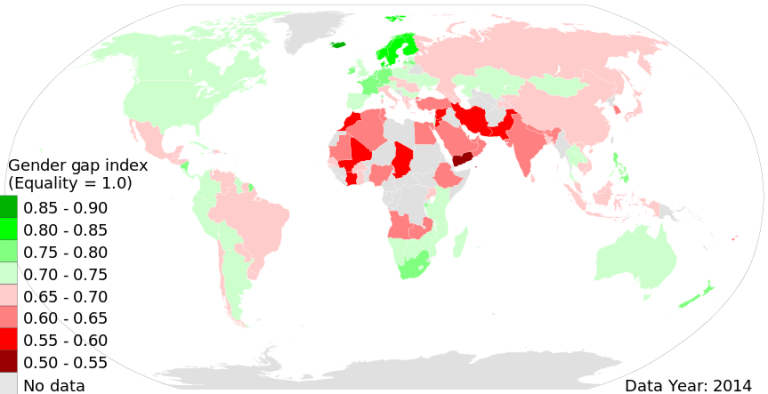

Karis, Mony and Franzi chose to research gender inequality for their Active Citizen Day (ACD), utilising the cross-cultural nature of our team to focus on both the UK and Cambodia. They began their peer education session by talking about the global gender gap index report from 2015, an index that gives every country a score from 0 to 1, where 0 denotes complete gender inequality and 1 denotes complete gender equality. Each country is then also ranked from 1 to 142, in order to allow comparisons between countries to be made.

According to the index, Iceland is the most gender equal country. Iceland, Finland and Norway have closed over 84% of their gender gaps. On the other end of the ranking, Yemen falls in last place with a score of just 0.51.

The report examines four overall areas of inequality between men and women in economies around the globe, covering over 93% of the world’s population:

- Economic participation and opportunity – outcomes on salaries, participation levels and access to high-skilled employment

- Educational attainment – outcomes on access to basic and higher level education

- Political empowerment – outcomes on representation in decision-making structures

- Health and survival – outcomes on life expectancy and sex ratio. In this case parity is not assumed, there are assumed to be less female births than male (944 female for every 1,000 males), and men are assumed to die younger. Provided that women live at least six percent longer than men parity is assumed, if it is less than six percent it counts as a gender gap.

Thirteen out of the fourteen variables used to create the index are from publicly available “hard data” indicators from international organizations, such as the International Labour Organization, the United Nations Development Programme and the World Health Organization.

Between 2014 and 2015, 10 countries experienced a worsening score – including the UK. Currently, Cambodia is ranked 108th and the UK is ranked 26th. Both the UK and Cambodia score most poorly in political empowerment. Whilst education is bad in some areas for Cambodia, most notably in the percentage of girls going on to university (12%) from secondary school compared to boys (20%), in the UK there is a reversed shift – education provision favours females, creating educational gender inequality towards males, since girls are 36% more likely to go to university than boys. Furthermore, disadvantaged girls ar 55% more like to go to university than disadvantaged boys.

In the UK, gender inequality is growing, especially in terms of employment wages and incomes, with women consistently receiving less pay than men in similar job positions. Wages are also lower as more women take up public sector positions, whilst men tend to take up more private sector positions which allow for higher wages and greater occupational mobility of labour. More men also go into academia and study subjects such as science and maths, perhaps because there are a lack of female role models in these areas.

In Cambodia, women are traditionally encouraged or expected to complete household work and assist in agriculture, and this might contribute to their lower levels of education compared to males. Additionally, school provision in Cambodia is often not fantastic, and women are discouraged from travel far to attend school due to the cultural norms of the country. Additionally, the average age of marriage in Cambodia is lower for women (22) than for men (25). This means that the age of marriage may disrupt a woman’s education, causing her to shun university education for family life.

The global gender gap index report is not a faultless measure of inequality, and many people complain that its tendency to compare countries distracts from the focus to make individual changes. Some people believe that each country should look at its own strengths and weaknesses in order to improve, rather than praising itself for small improvements in scores or rankings over times. To change cultural norms and attitudes takes a lot longer, and is a lot harder, than merely producing a change in statistics.

Written by Kate Goodrum

Photo of female students at Crocodile Primary School by Karis Lambert